The old cemetery on the grounds of the ruins of Ahamore Abbey on Derrynane beach in Co. Kerry is a beautiful place to be buried.

Accessible at low tide, many a coffin has been shouldered onto Abbey Island. There’s a bench there, overlooking the strand, facing out towards the Atlantic, right beside a headstone inscribed with the name Dwyer (my mother’s side of the family).

Further in, there’s another gravestone etched with the names James and Catherine Murphy. This, coming so soon after my parents died, made this visit all the more special.

Both names are popular in Ireland but Abbey Island lends itself to flights of fancy.

It’s here, too, in the grounds of the ruins of the sixth-century Abbey of St Finian that Daniel O’Connell’s wife Mary is buried.

Their marriage had an interesting start. As Mary was rather penniless, his family was against the marriage. But O’Connell was determined. They married in secrecy and kept it a secret until Mary got pregnant. There was no hiding that.

Mary O’Connell’s grave – top left

I was taken with the mix of Irish and English inscriptions; it wasn’t surprising as Kerry is one of Ireland’s Gaeltacht areas. It was lovely to see, though, as was the old Irish script, much favoured by my father.

Trans: Eternal peace to your soul; may we live in this place again

Trans: Eternal peace – may we be caught in God’s nets

I lionta Dé go gcastar sinn is a line from the hymn Ag Críost on Síol, synonymous with St Patrick’s Day. It was one of the many references to the close connection with the sea in this part of Ireland.

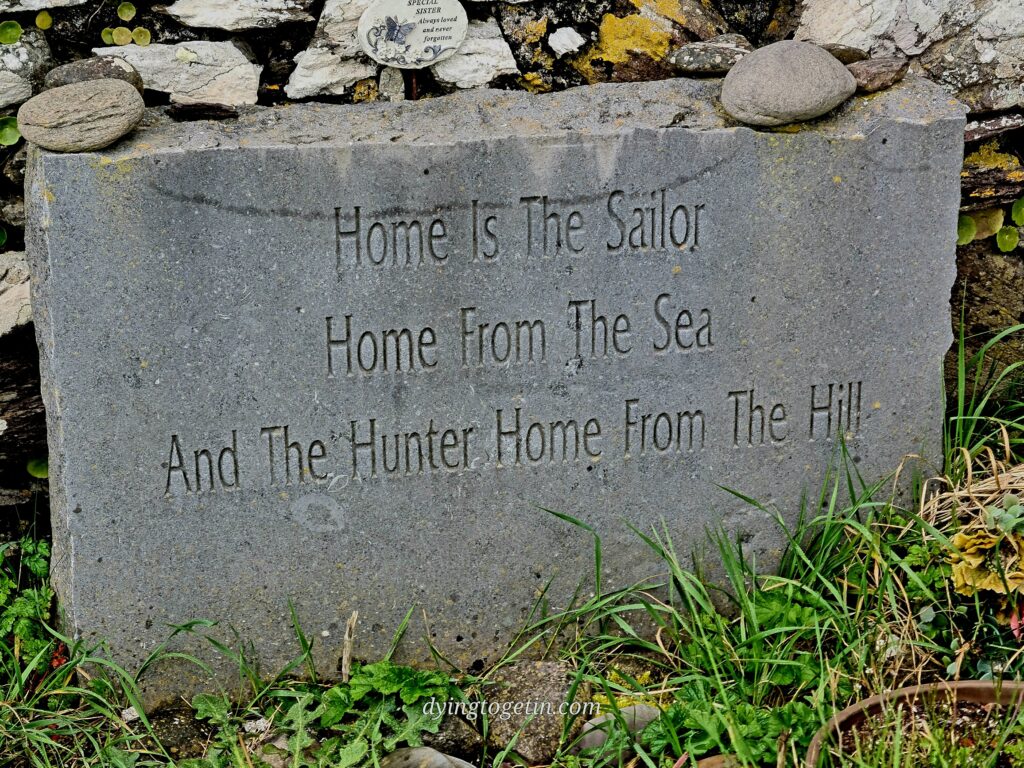

From the poem Requiem by Robert Louis Stevenson

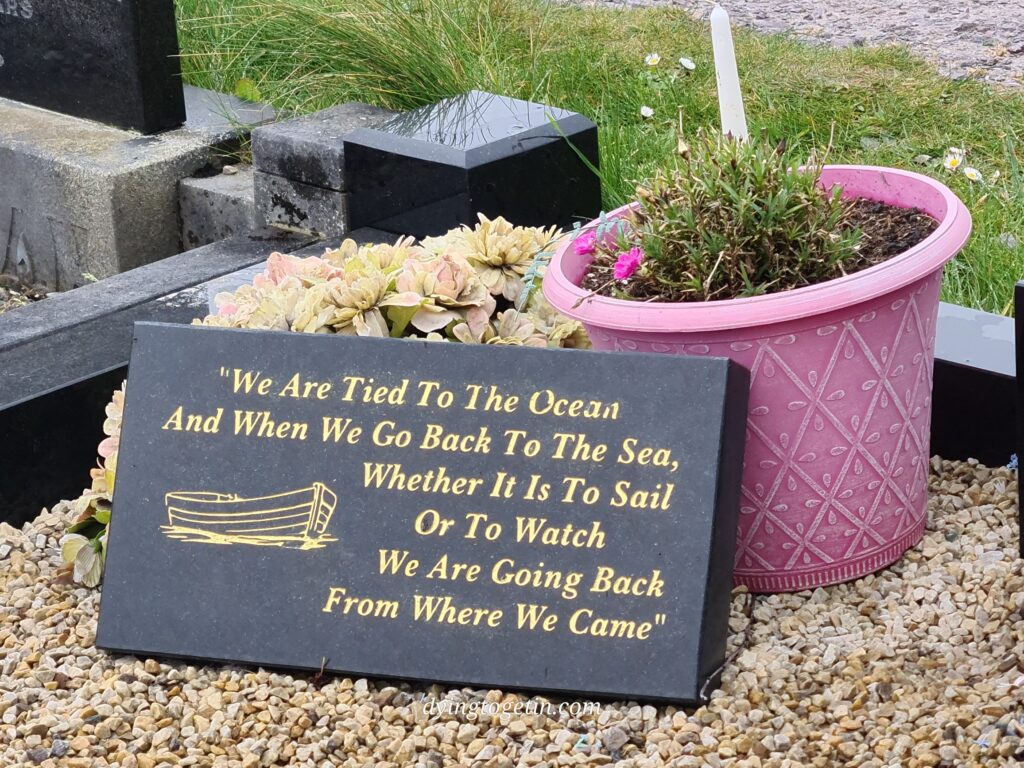

Quotation from John F. Kennedy at the 1962 America’s Cup dinner

The American connections are in evidence, too. Sadly, I can’t find anything about Patrick O’Sullivan and how he ended up in the US Army or indeed, how he came home. All I could find is that he was married and died of a brain haemorrhage.

The same for Humphrey O’Sullivan, although I wonder if he was any relation to the hedge-schoolmaster and crony of Daniel O’Connell, Amhlaoibh Ó’Súillebhán.

In the background of this photo is the grave of Mary Fenton White, the third WWI veteran buried in Derrynane. She was in the Army Nurse Corps, born in 1892 and died on St Patrick’s Day in 1962. She came home and married a farmer and would die of a fractured hip. And not all that long ago either.

The Celtic Crosses against the skyline stand tall and proud. Even though the day was dull, they shone. Weathered stone ages beautifully.

Elsewhere, looking out over the Atlantic, other gravestones stood straight, some at an angle, beaten down by the wind and the rain. It’s a magical spot.

Mary and Timothy O’Sullivan lost three of their children; only the fourth outlived them (see alt text for full inscription)

So many stories. So much history. I’d like to go back and find someone in the know.

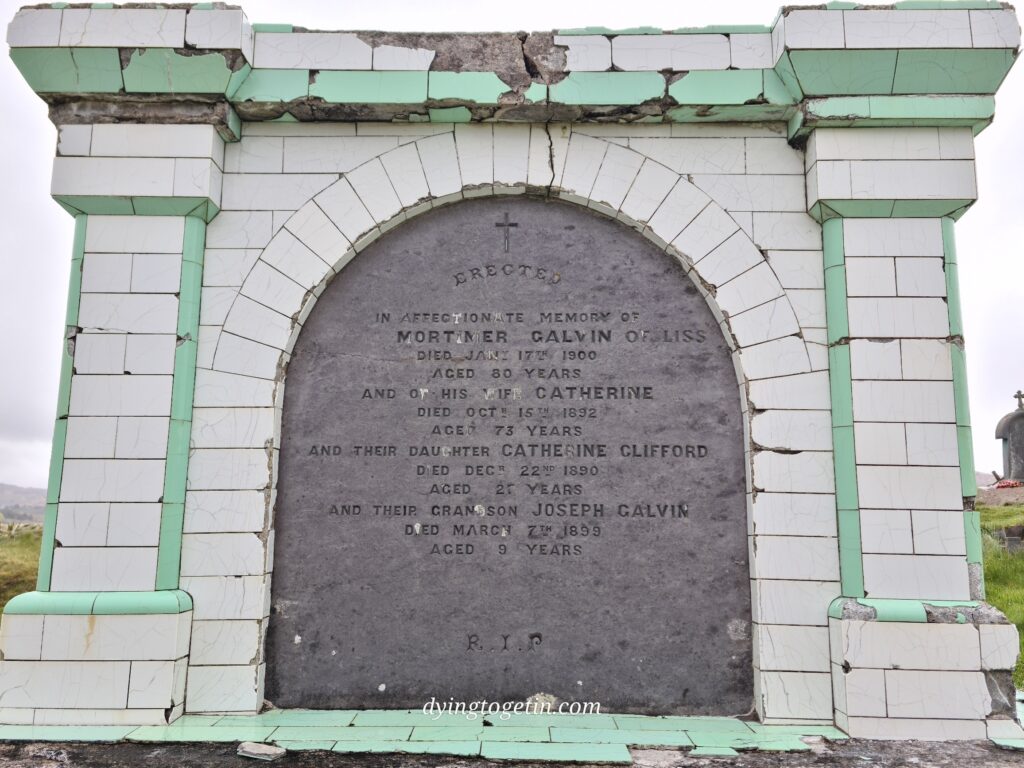

Apart from the O’Connell tomb (which has the oldest grave in the cemetery from 1770 and is still in use with the most recent burial in 2007) and one other overgrown, a third stands out. The Galvin Family tomb. The green and white tiles are a 1950s addition (according to a survey by Kerry County Council) yet the burial dates go back to 1892. Sadly, Mortimer (who himself died from apoplexy) and Catherine Galvin (who died from bronchitis) lost their only daughter Catherine in 1890 and their grandson Joseph in 1899 (aged 9). Catherine herself died in childbirth having only married a year earlier. So much life. So much tragedy.

And then, there’s the gravestone that makes you smile and leaves you wondering.