As a child in the 1970s, I remember June as an ambiguous time. Crowds would come down from the North to commemorate the death of Wolfe Tone, the founder of the United Irishmen and the ‘first leading light of Irish republicanism’. The laying of the wreaths by balaclava’d men was something I never got to see. I knew of it because my dad, a member of the Garda Siochána, was always on duty. I remember it as a series of Sunday commemorations ending in the one closest to June 20, the date Wolfe Tone died.

An account of the history of the commemorations dates it back to the 1800s, with various peaks and troughs depending on the popularity of the republican movement. The 1970s and early 1980s saw heavy traffic.

At home for Christmas, I stopped by to see the graveyard to see the place where it all happened.

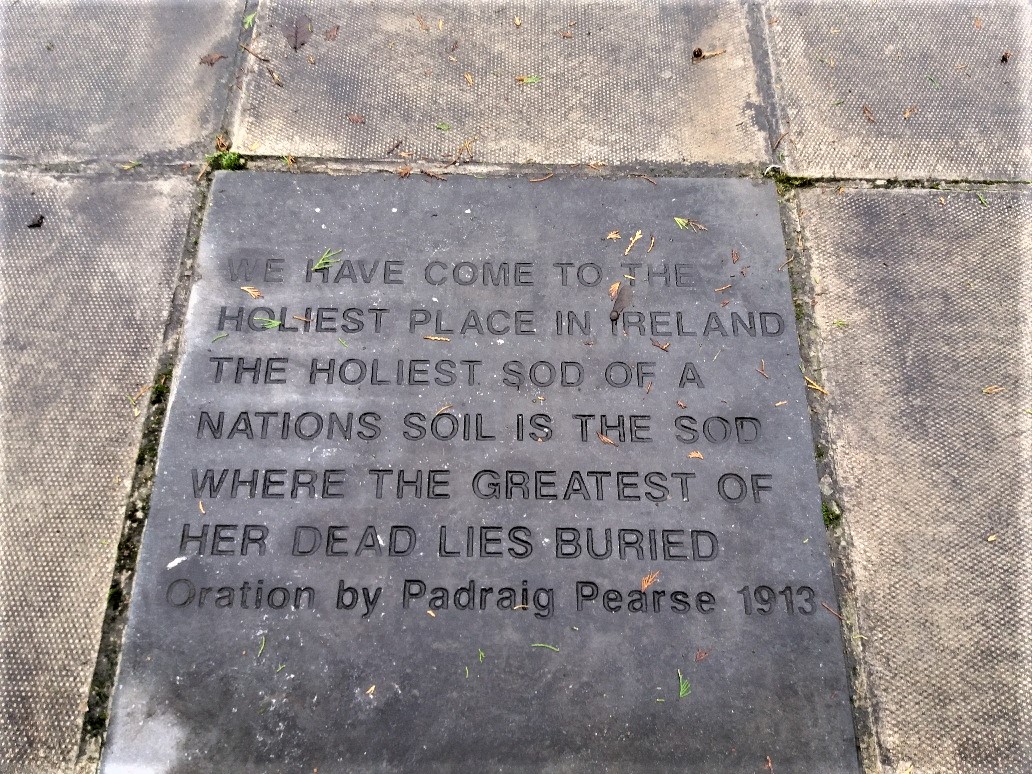

It’s an odd little graveyard, with a mix of older headstones toppling over and new, more recent plots dressed for Christmas and well-tended. The five flag poles have memorial plaques at the bases, four of them noting the executions of republicans Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Richard Barrett, and Joe McKelvey, all executed as retribution for the killing of TD Sean Hales by the anti-treaty IRA in 1922. In a fascinating turn of fate, the execution order was signed by Kevin O’Higgins. Rory O’Connor had been best man at his wedding the previous year. Such was the madness of that era. There was something quite eerie about seeing the word executed, particularly repeated as it was four times.

There’s a small side gate from the main road and as you wander in the pathway, you’ll see a marker for Private Duffy who died in 1918. Curious to know more, I searched for him online and found this:

Duffy, Walter. Reg. No. 10675. Rank; Private, Leinster Regiment, Depot. Died home, July 7, 1918. Born Naas, Co. Kildare.

While there was just the one poppy cross and no flowers, the gravestone itself was in remarkably good shape. And I wondered.

Next to the ruined church, to the left of the five flagpoles, there’s a replica of the dock from which Wolfe Tone gave his final address after pleading guilty to the charges brought against him. In it, he asked for death by firing squad but was sentenced to death by hanging. Historians seem to be in agreement that Tone died from a penknife wound of his own making. And yet he’s buried in consecrated ground, unusual for those who committed suicide in those days.

In this small graveyard, nestled between the villages of Clane and Sallins, lies a chapter of Irish history that includes in its list of visitors those who come to remember. The group, the Wolfe Tones, have immortalised the graveyard in song. The words, written by Thomas Davis after he visited the grave in or around 1843 and found it unmarked but guarded by a local blacksmith who wouldn’t allow anyone to set foot on it.

Wolfe Tone and the culture of suicide in eighteenth-century Ireland

Wolfe Tone’s speech from the dock