Back in seventh-century Ireland, a chap who’d later be known as St Finian of Innisfallen, happened upon this part of the world and set up a monastery. Whether he was St Finian Cam or St Finian the Leper, the Internet is undecided.

Fourteen centuries later, the remains of his church can still be seen amid the many graves of the Old Kenmare Cemetery.

Almost opposite the very-much-alive Sheen Falls Hotel off the Glengarrif Road, it is a special place for many reasons.

Some 5,000 bodies are buried in the famine plot. And to think that nearly two centuries later, people are still dying from famine in other parts of the world.

The United Nations tells me:

Each day, 25,000 people, including more than 10,000 children, die from hunger and related causes. Some 854 million people worldwide are estimated to be undernourished, and high food prices may drive another 100 million into poverty and hunger.

And while, on a macro level, 5000 over a few years seems rather paltry, that arguably it wasn’t a shortage of food that caused the famine but an unwillingness to share still rankles. This and other famine plots like the one in Naas cut me to my core. Have we learned nothing?

I stopped for a while too, at the cillíneach, where unbaptised children were buried until the early twentieth century. Thankfully, this separation is no more.

A tricolour caught my eye. The inscription on the gravestone of one Lieut. Denis Tuohy hints at his politics. On leaving the Royal Irish Constabulary to join the IRA, Touhy was at one stage a bodyguard for Terence McSwiney, himself no stranger to the world stage.

At the end of his court-martial on August 16th, 1920, Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork, greeted his sentence of two years in jail by declaring: ‘I have decided the term of my imprisonment…I shall be free, alive or dead, within a month.’ Four days earlier, British troops had stormed the City Hall in Cork and arrested MacSwiney on charges of possessing an RIC cipher and documents likely to cause disaffection to his Majesty. He immediately began a hunger strike that sparked riots on the streets of Barcelona, caused workers to down tools on the New York waterfront, and prompted mass demonstrations from Buenos Aires to Boston. Enthralled by MacSwiney breaking all previous records for a prisoner going without food, the international press afforded the case so much coverage that Ireland’s War of Independence was suddenly parachuted onto the world stage, and King George V was considering over-ruling Prime Minister Lloyd George and enduring a constitutional crisis. As his wife, brothers and sisters kept daily vigil around his bed in Brixton Prison, watching his strength ebb away hour by hour, MacSwiney’s fast had Michael Collins preparing reprisal assassinations, Ho Chi Minh waxing lyrical about the Corkman’s bravery, and rumours abounding that he was being secretly fed via the communion wafer being given to him each day by his chaplain.

The things you learn from cemeteries.

On the other side of the civil war were the O’Connor brothers, killed during the months the IRA had control of the town of Kenmare: September to December 1922. Of all types of war, civil wars have to be the most difficult for mothers, pitting brother against brother and tearing families apart. Seeing your sons fighting on opposite sides, like Kerry brothers Thomas and Patrick O’Donoghue, what are you to do? The Civil War in this part of the country was particularly violent and memories are long.

Walking through the field of graves, I happened upon a more recent memorial to the O’Shea family. I suspect someone was researching their family tree. Look at how young they were.

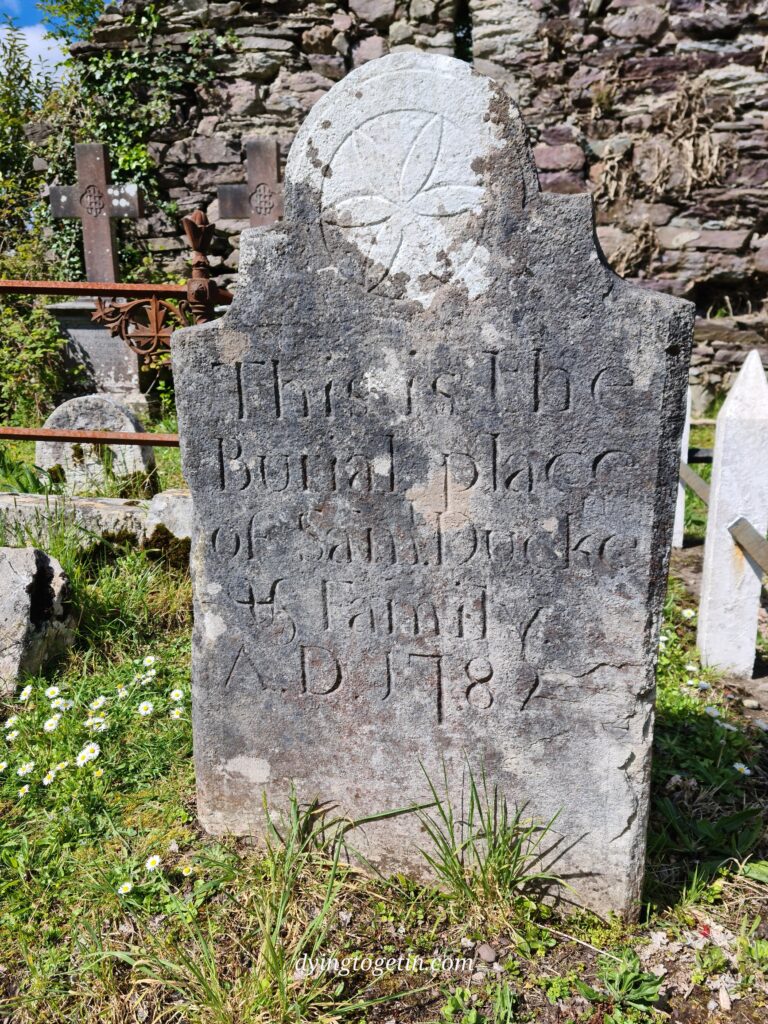

Farther on, over near the church ruins, I did a double-take on reading this. Could it be that a saint is buried here? St Ducke? It took a while but this particular rabbit hole led me not to saintliness but to the family of one Samuel Duckett, whose daughter Petra (an unusual Irish name I thought – I know three, two Hungarian and one Swede) married one Bastable Maybury. Ye gads!

Going back to St Finian and which of the Finians he was, the plaque by the gate says:

St Finian Lobhar (the Leper) came from Leinster; he took on the disease of leprosy to save the life of a friend and was directed to this well for its curative powers.

The holy well behind the graveyard by the water is a popular site every year on 15 August when locals come to take water to cure eye ailments and warts. Coincidently, or not, 15 August is the day of the annual town fair.

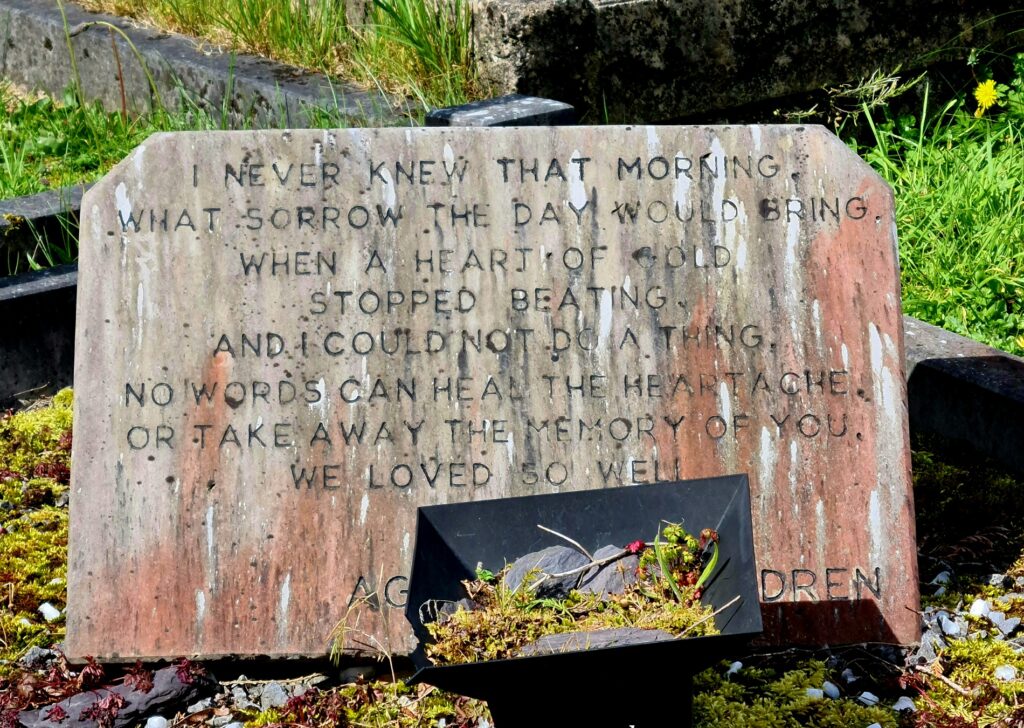

It’s a lovely spot. Lots of wildflowers among the ageing gravestone, many leaning over with age. As with many old cemeteries, there are lessons to be learned from the sentiments and epitaphs.

.