A dead man here. Another one there. This one in his 60s. The other in his 80s. Beloved father, husband, son. An inevitability. Yet to see the markers of 211 dead RAF men, all of whom died within a few years of each other. Some on the same day, at the same time even, and none older than 36. That’s not inevitable. That’s war.

The British War Cemetery is about 14 km outside of Budapest in Solymár. Not all of those buried there were British RAF (128). There are Canadians (6), Australians (13), New Zealanders (6), French (1), South Africans (20), and Polish (37), all RAF men shot down in WWII. It’s one of the most inspirational places I’ve seen in a long time.

Just inside the gate, there’s a register of graves, with each man’s name, rank, and family details inscribed. Those who went down in the same plane, on the same day, are buried side by side. It gives it perspective somehow.

Except for one French cross, and the 37 Polish headstones that have a pointed top, all of the markers are the same curved white stone.

The two Jewish graves have the tell-tale pebbles – which surprised me – as one was Canadian and the other South African. It does this occasionally jaundiced heart some good to know that someone, somewhere, still cares enough to pay their respects.

The cemetery itself is beautifully maintained, as all Commonwealth graveyards are, thanks in no small part to Sir Fabian Ware, who founded the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Too old for active service at the age of 45, he went to France with the British Red Cross in 1914. It wasn’t long before he noticed that there was no system of recording the graves of those who had died in battle. He convinced the War Office that if the dead were properly looked after, it would boost the morale of the living. [I’m still trying to work that one out, but I suppose in an odd way, it makes sense. So much of what we see today still testifies to the need for closure; that need to know where the bodies have been buried.] His motivation? Common remembrance of the dead [of the Great War] is the one thing, sometimes the only thing, that never fails to bring our people together.

Admittedly, I wasn’t thinking of Fabian Ware or his Commonwealth War Graves Commission, as I walked each line of headstones. I was taken by the lessons to be learned from their inscriptions.

How many of us think in terms of a finished life? Of an end date by which we should accomplish all we have set out to achieve? Of a finite point in time when the clock will stop and our time will end? A preoccupation with such thoughts might be debilitating rather than motivating, but a healthy awareness of the inevitability of death might encourage us not to waste what time we have now.

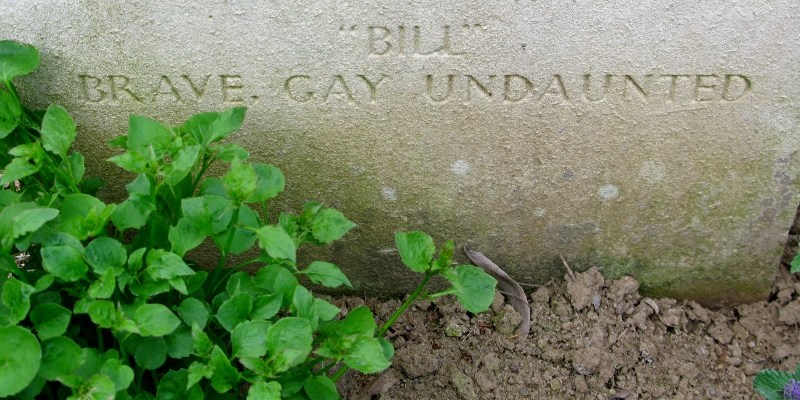

I doubt this is a comment on Bill’s sexual preferences, but I’d like to think that it is. And that we could learn something from this – learn to accept each other for who we are without judging.

The idea of sacrifice – how alien is that in today’s ego-centric, all-about-me world of likes and friends and followers? I am hard pushed right now to think of one cause that I would willingly die to defend. Oh, I’d like to imagine that I’d be in the thick of the resistance should WWIII break out. I’d like to think that I’d be helping the persecuted escape, standing up for justice, playing my part. But would I really? I sincerely hope I never get the chance to find out.

Back in the 1940s, choice was a luxury few enjoyed. If your number came up, you got a uniform. Today, young people enlist. Perhaps some are misguided and fall for the marketing hype (I’ve seen one recruitment video for the US military and even I was tempted). More, I hope, firmly believe in their country. Others still might be making calculated career choices rather than playing to their patriotism. But those who may end up on the front line deserve our respect and our prayers, regardless of our politics.

In opting to be cremated, I will be crossing one task off my list – that of thinking of what I’d have etched on my tombstone (yes, I’m organising my own funeral lest someone gets carried away with the pomp and ceremony and God forbid, chooses the wrong music for me to depart to). But this saddened me to the core. I’m not sure if it’s the fact that he is nameless, ageless, stateless, or just plain dead. I’d like to think that when I go, someone will notice me gone.

I smiled at this one, as I do every time I remember playing with the elephants. That trip to South Africa changed me. Not noticeably, except perhaps to me. I smiled because it conjured up swash-buckling images of dapper pilots heading to their planes, silk scarves flying behind them. The notion of pals. Of enduring friendships carved out of circumstances that no one should have to endure. Those friendships we make in times of shared adversity or hardship or grief – they are of a different mettle, a different type of bond. And these pals – they all went down together.

There’s something about this place that makes it special. I’m not an advocate of war. I don’t pretend to understand why people choose a life that is in large part dictated to them by others. I cannot fathom how anyone could follow orders that go against their conscience. But that’s neither here nor there. Seeing these men, aged 19 to 36, their markers standing to attention in the shadow of a big white cross, gave me pause for thought.

Kiev isn’t far from Budapest, literally and figuratively. Could what’s happening there, happen here? On a wider scale, are we due another great war? And if we did find ourselves in one, would we be able to cope? So many questions…